Asset Protection Guide for Orange County, California

Asset protection is about early, lawful planning to protect your home and financial stability, not hiding assets.

Asset Protection Guide for Orange County, California

As an asset protection attorney in California, I view the law as somewhat emotional, or maybe the correct phrase is "of two minds." We as a society both love and hate the concept of "asset protection." When anyone in California considers doing their own asset protection, they need to think about not just their own interests but how society will view those actions. In asset protection, there is a line between what is considered good and beneficial policy and what might get a person into prison.

As a society, we want to have a functioning civil justice system. That means that if an individual cheats their business partner, dumps toxic waste near a public elementary school, or gets drunk before scrubbing in to do surgery causing serious medical complications for a patient, we want them to pay for the harm they caused.

We also don't want people living on the public till or being homeless. Beyond this, as a society we do want businesses to flourish (so that they can pay taxes) and for people to retire in dignity.

Other jurisdictions outside of California will see their public policy goals somewhat differently. Instead of dialing "creditor friendly" they will be "debtor friendly." That means that they will be more likely to not want to enforce a judgment under certain circumstances than California. Their interest is to get more trust and LLC business into their states or foreign nations. The question then becomes: if you live in California, does that work?

The purpose of this guide is to demystify the process of "asset protection" for Californians who want to do the right thing for themselves and their families and potentially the employees that rely on them for the functioning of their businesses. They want to continue to live in their homes and hold onto as much of their wealth as possible even if some sort of financial calamity such as a massive lawsuit (or series of lawsuits) or even bankruptcy threatens them with poverty.

Basic Protections You May Already Have

Engaging with an asset protection attorney is not going to be a fruitful endeavor for individuals with assets that might already be situated in a way that already protects them. For example, Athena works as a nurse in Orange County. She has a pension, a 401(k), a house with $500,000 in equity, a bank account, and a brokerage account. Her employer provides her with adequate liability insurance.

In Athena's case, it may not make a lot of sense for her to engage with an attorney for asset protection planning. The planning itself might be too cumbersome and expensive in exchange for benefits that might not be there, at least not yet. This is because Athena's house is reasonably well protected because of the California homestead exemption. Her retirement accounts are protected through a federal law known as ERISA. Her bank and brokerage accounts don't have the same protections, but as I will discuss, part of any asset protection plan is maintaining a level of solvency. Athena may need that money for emergencies, vacations, and other plans.

Athena may create a revocable living trust for probate avoidance and incapacity planning as well as other estate planning documents, such as a last will and testament, power of attorney, and healthcare directive. These do not provide asset protection, however they are what responsible adults should do.

Asset Protection Is More Like Asset Defense

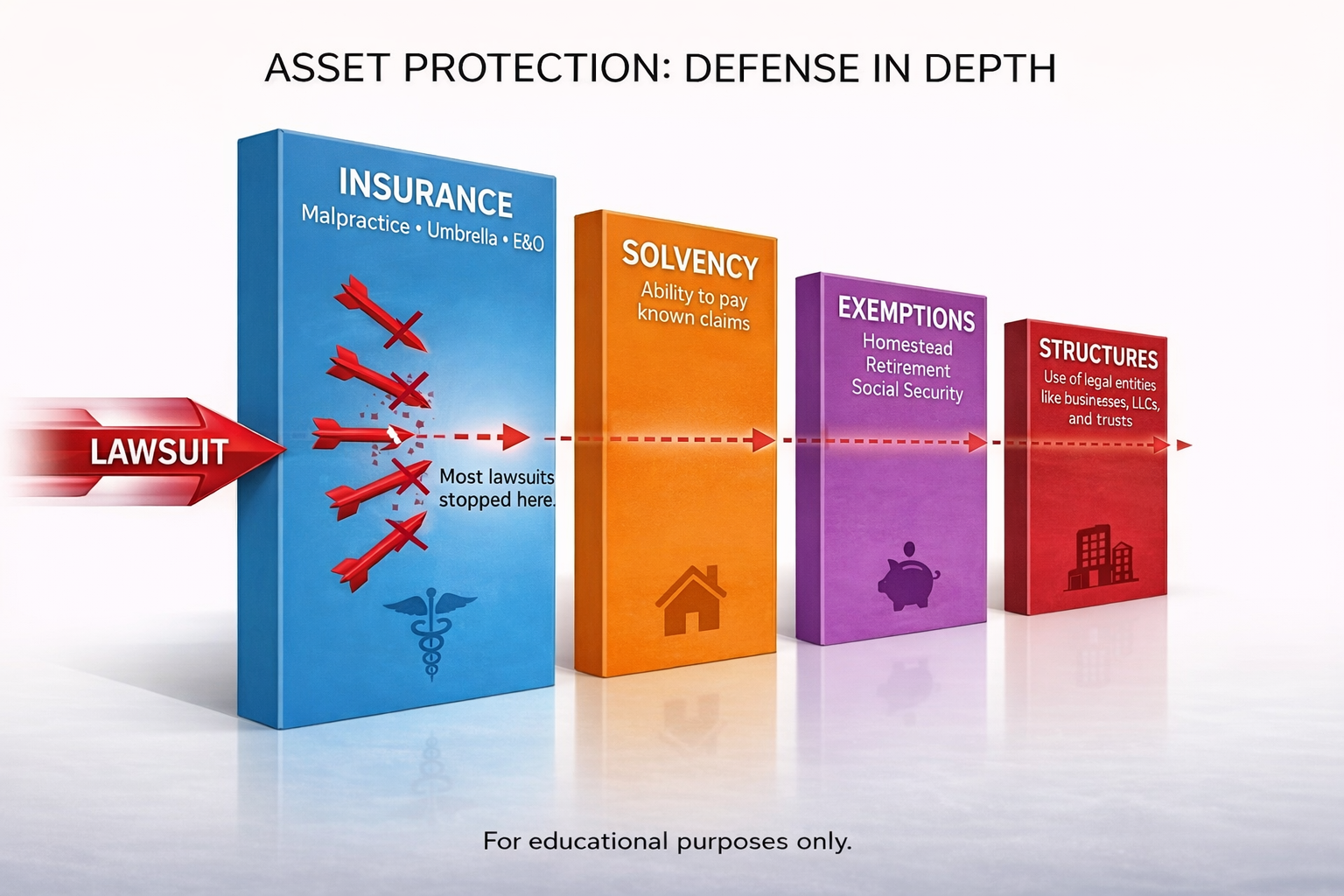

For business owners and individuals in high-risk professions—medicine, law, real estate, contracting—California courts are busy with lawsuits against people like them. For these individuals, it is best to think about asset protection as building defenses against future threats. In many instances, building these defenses is well within the confines of California law. In some cases, we may need to reach outside of California law in order to better protect certain assets so that the laws and public policy goals of those other jurisdictions will take precedence over what might be available under California law.

The process of setting up any asset protection is itself a perilous endeavor. Remember, any action that you take, anything that you tell anyone, unless it is protected by attorney-client privilege and work product, might be available to a future judgment creditor. By itself, doing asset protection planning is not considered to be shady or shameful under California law or anywhere else. It is the responsible thing to do for a person with wealth who is concerned about future threats against that wealth. As I will discuss below, the problems come about when a future judgment creditor claims that there was a voidable transfer, a fraudulent conveyance, or potentially something even more nefarious that might be a crime. We will get to that.

Building the Defense: Start with Insurance

Asset protection planning is a complex area of law with many tripwires and ways that you can get in trouble. However, the first layer of defense is not complicated at all. It is probably something that you, the reader, already have—insurance. Just because you have insurance doesn't necessarily mean that you have the right kind of insurance, or that you have enough insurance, or that when a problem comes about, the insurance will actually make payment on the claim.

Insurance contracts are not one sentence long. They typically include a variety of reasons why they won't pay you. In some instances, the law simply will not allow you to insure against certain types of lawsuits because it is against public policy. For example, an insurance company is not going to sell a man an insurance policy that will pay claims in the case of sexual assault.

One other consideration with insurance is the financial strength of the insurance company itself. In the past several years, insurance companies have been purchased by private equity firms and there has been criticism that this has weakened the financial position of insurance companies. So, when the time comes to pay a legitimate claim, the money may not be there.

The good news about insurance is that there are many quality insurance companies available that are likely to be able to make payments when the time comes. Most of the claims that insurance companies pay are the very kinds of things that people who want to do asset protection are worried about, like professional liability.

The concern though with professional liability insurance or with business insurance is that there is a hard dollar limit on how much the insurance company will pay. The amount an insurance company will pay often includes legal fees. For litigation cases that last for many years, attorney fees alone can easily go into millions of dollars. That may intrude into policy limits, or exceed them. Anyone considering asset protection should consider whether their insurance policy is large enough to both cover the cost of modern litigation fees as well as the kinds of damages that you might expect. Of course, damages can be significantly larger than what you might expect. Examples that I have seen include:

- Children in rental property microwaving ramen noodles cause an entire neighborhood to burn down.

- A home restoration specialist is sued by a neighbor who complains about a crack in his swimming pool from the construction activity. Litigation goes on for years and results in bankruptcy.

- A man mows his lawn, causes a named forest fire.

Plaintiffs' attorneys, from medical malpractice to injury attorneys, frequently brag about the exceedingly large judgments that they can obtain. For many of these judgments, insurance was simply not enough.

Solvency: Does Not Feel Like Protection, but It Is

In explaining this part of asset protection, think of it this way:

If David, an Irvine small business owner sues Goliath, a Newport Beach surgeon and wins, and Goliath has money in his bank account, David can probably get it. If Goliath has no money but his mother Oprah does, David probably cannot get it. There is an area between those two hypotheticals where asset protection planning resides.

However, for anybody who is going to do any kind of asset protection, there has to be some credibility associated with it. There must be good faith and there has to be a demonstration of a desire that the person who is creating the asset protection is "with the program" when it comes to agreeing that people should pay for civil wrongs and that any responsible planning that they did took into account the fact that they should have some money lying around in case things go wrong, at least what they can reasonably foresee.

Say, for example, Goliath punches David. David tells Goliath he is going to sue for the intentional tort. Goliath then moves his assets to an irrevocable trust for the benefit of his mother, Oprah. As you can guess, this is unlikely to work.

Fraudulent Conveyances and Voidable Transfers

California's response to Goliath's last-minute trust is the California Uniform Voidable Transactions Act. The statute gives David a tool to undo transfers that were designed to cheat him.

The law recognizes two flavors of bad transfer:

Actual fraud is what Goliath did. He knew David had a claim. He moved assets specifically to keep David from collecting. Intent is the key. A court doesn't need Goliath to confess—circumstantial evidence is enough. Courts call these "badges of fraud." So if Goliath transfers property to his mom, does it in secret, sells it for a bargain price (like a dollar), or the transfer happened after David's lawyer sent a demand letter, these would be bad signs.

Now if Goliath decided that he was going to do an asset protection plan, transferred his wealth into a responsible structure (we will get to that) and maintained a level of solvency that made sense for his situation, he would be in a better position. Now, if he got angry and punched David, and David sued him, David is less likely to be able to come after the Goliath's assets. Yes, David can collect insurance, he may be able to collect against some of Goliath's wealth, but there would be a defensive line after which David can go no further. He is stuck. Even if he has a judgment that far exceeds what the insurance might pay and makes Goliath insolvent, he may not be able to collect whatever else Goliath socked away.

Time Matters

There is a misconception about statutes of limitations in asset protection. People assume their planning isn't effective until the clock runs out. That's not how it works.

Consider Goliath again. In year one, he creates an asset protection structure—an LLC, a trust, whatever makes sense for his situation. At that moment, David doesn't exist as a creditor. There's no punch, no lawsuit, no claim. Goliath isn't trying to defraud anyone because there's no one to defraud. The transfer is legitimate when made.

Year three, Goliath punches David. Year four, David sues. Now David has a judgment, and he wants to unwind that year-one transfer. But David has a problem. Goliath wasn't hiding assets from David. Goliath was doing responsible planning years before he ever met David. The badges of fraud aren't there. The intent isn't there. David is stuck.

This is why timing matters more than technique. The structure Goliath used is almost secondary to when he used it.

California's specific deadlines: four years from the transfer for actual fraud, with an extra year if the creditor couldn't reasonably have discovered it. Four years for constructive fraud. And an absolute backstop—Civil Code Section 3439.09 says no action can be brought more than seven years after the transfer, regardless of anything else. That seven-year statute of repose is one of the few bright lines in this area of law.

Other jurisdictions set their own clocks. Bankruptcy court uses a ten-year lookback for fraudulent conveyances—longer than state court and with different tools available to the trustee. Nevada's statute runs two years. Ohio's runs eighteen months. The jurisdiction matters.

Some underlying claims have exceedingly long statutes of limitations. Claims involving minors can be tolled for decades. A surgeon who operates on a child today might face a malpractice claim twenty years from now. A contractor whose work fails might get sued fifteen years later on a latent defect theory. Construction defect claims in California can surface ten years after completion. For people in these professions, "plan early" isn't just good advice—it's the only way the time element works in their favor. They need their planning to predate claims that haven't happened yet and might not happen for years.

Even if these individuals are sued, California and the federal bankruptcy system allow for exemptions from collections. This is fundamental to planning since everyone with wealth wants to make sure they are optimally structured so they can continue to live in dignity, even if there is a devastating lawsuit or bankruptcy in the future.

Exemptions

One of the most important exemptions that you have is your home. There is a solid societal interest in not wanting to make people homeless. Unlike Texas or Florida, the home is not absolutely protected but instead is protected based on a dollar amount. The amount of the value of the house that is going to be protected is based on the average price of a home in a given county up to a maximum, which is presently over $700,000 (it adjusts for inflation every year).

Many Californians have equity that exceeds this amount. For them, families will generally have to either consider it not being protected or take actions that are coordinated with more advanced asset protection strategies so that either the equity in the home is less than the threshold or the home is an unappealing asset for any collector to take away.

For bankruptcy purposes, there are some restrictions that would cause people to lose their home more easily since there is a federal cap of around $214,000.

Federal law does help out when it comes to retirement plans in a way that it does not seem to when it comes to homes. Under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, or ERISA, retirement accounts are protected from both lawsuits and bankruptcy. What most people think might be covered by ERISA—IRAs and Roth IRAs—are actually not. They are protected under state law. Under California law, the actual level of protection that these accounts provide is somewhat speculative. Relying on these accounts for asset protection is often not going to be a good strategy.

California does however have something called a private retirement plan under CCP 704.115. This is unique to California and allows for individuals to set up a private retirement plan protected "to the extent necessary to provide for the support of the judgment debtor when the judgment debtor retires and for the support of the spouse and dependents of the judgment debtor."

One important aspect of this type of planning is that it is protected under California law. California residents should generally not overlook this type of protection in favor of other jurisdictions. Other jurisdictions are certainly valuable in the right context, but in general, California residents should always plan around California law first.

Business Entities

There are strong public policy reasons why society confers asset protection benefits to business entities. The kind of protection that they provide is going to vary depending on the type of entity, the law, and the ownership and management structure.

The type of asset protection provided by a corporation is probably the one that most people are familiar with.

Say, for example, Hercules owns 1,000 shares of Apple stock. His risk in the ownership is the value he invested in the stock. If Apple is sued and loses a lawsuit, the judgment creditor is not going to come after Hercules. The litigation affecting Apple is not going to bleed over into Hercules's bank account. However, if Antaeus sues Hercules for professional liability and Antaeus wins, Hercules may lose that stock. What this means is that while Hercules has "inside-out" protection, he does not have "outside-in" protection.

Other business entities, such as a limited liability company or a limited partnership, may do this better. I say maybe because this is a function of state law as well as the design of the business entity itself.

An individual is always liable for the actions that they themselves take. So, for example, if Hercules is a surgeon with a medical corporation, and he operates on Antaeus and now has professional liability, Hercules does not have the "Apple defense" here and cannot claim that the professional liability should be relegated to his professional corporation. If Hercules has assets that he personally owns, those assets might well be vulnerable.

The key then is what he might do to protect them.

Use of Trusts

Say Hercules wanted to create a trust, placing millions of dollars in it. He named somebody else as the trustee of the trust but was the beneficiary himself, so he could always have access to this money. The idea behind the trust is that if he gets sued in the future—professional liability, intentional torts, whatever—too bad for those people. The assets of the trust will not be used to pay those claims. That is against public policy in California. We have something called the "self-settled trust doctrine" that prevents Hercules from doing exactly that kind of thing.

However, this kind of strategy is not against the public policy of other states and foreign jurisdictions. It is common for individuals to create trusts and business entities in other jurisdictions while at the same time expecting that this is going to work in California.

Say, for example, Hercules has a rental property in California, owned by a limited liability company in Wyoming. This limited liability company is in turn owned by another limited liability company in the offshore jurisdiction of Nevis. That Nevis limited liability company is owned by a trust in the Cook Islands where Hercules is the beneficiary. If Antaeus wants to collect a professional liability judgment against Hercules by getting this rental property, Hercules, if he got in front of a judge, may say Antaeus cannot do this because Cook Islands law does not permit this. A judge may easily point out that we are not in the Cook Islands.

If a California court can get to it, California will decide what the rules are.

Trusts in other jurisdictions, particularly foreign jurisdictions but also domestic jurisdictions such as Nevada, can be a useful tool in the right set of circumstances. When you create your asset protection defenses, it is important to properly design what type of defense goes where. Building a fortification to defend yourself with your water source exposed to your enemies just outside is bad design that will end badly. Orange County courts will not play “Simon says” with foreign laws when the law here allows them to just take your stuff.

Any responsible asset protection looks at it from a perspective of not merely having a "trust," "LLC," or "exemption" but also how the structure, as designed, can withstand scrutiny.

An asset protection attorney needs to ask the right questions, game out scenarios where failure may take place, and plan for appropriate contingencies.

We all want to make sure we fulfill our responsibilities to society. At the same time, we want to protect what is ours. That is an instinct that has been with us for thousands of years.

To discuss asset protection planning, schedule a consultation with Attorney Ahmed Shaikh.

.jpg)